Libertarianism is often a lonely path to follow. While this may be befitting of its individualist nature, it is intriguing to find how others have reached the same conclusion as you. I thought I’d document my own personal journey as an example of this.

I grew up in a household where my parents frequently argued over politics. My father was a union man and hence a Labour supporter, his best friend was Father of the Chapel (the title for a Shop Steward within SOGAT, the print union) at their employer; my mother was a Conservative supporter and had a strong anti-socialism streak. This left me with conflicting information about who was the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ party of the two, but also gave me a healthy appetite for debate.

Growing up in the 1970s and early 1980s was an interesting time to observe politics in action: power cuts in the evening; the miners’ strike that brought down Edward Heath; joining, and then nearly leaving, the EEC; the increasingly disastrous government of Harold Wilson then James Callaghan; the 1976 IMF bail-out loan and associated cuts; the Winter Of Discontent; the election of the first (and so far only) female Prime Minister; the Falklands War; numerous recessions; the Brixton riot and subsequent Scarman report; and the miners’ striking (yet again). These domestic challenges demonstrated to me at an early age the destructive power of politics and I developed a distrust of all politicians.

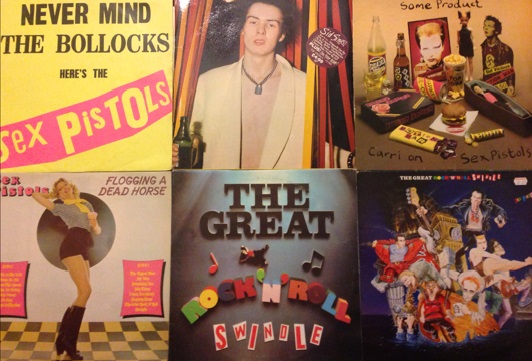

During this period the UK Punk scene began and I immediately found it appealing, the antithesis of the tired prog-rock and disco music that was prevalent at that time. I became a devotee of the Sex Pistols (still am) and quickly adopted their professed ideology Anarchy, scrawling its infamous logo across all of my school exercise books.

I tried to read what little material I could find on the topic, but other than John Lydon’s brief rants, there was little available at my shoddy state comprehensive’s library. What did confuse me was why Lydon seemed to be advocating some form of socialism, when in my mind anarchy was an absence of state, so how can anarchists want more government, not less? It was nearly a decade before I was to discover anarcho-capitalism. In this period one book we read in English at school stuck with me: Animal Farm, by George Orwell; It led me to read Nineteen Eighty Four, which was a revelation.

My mother’s political views instilled a distrust of socialism in me, and at this stage of my life I had already planned to be a millionaire as an adult (note to that 11-year old: still waiting) so I wanted to retain my earnings. My mother had explained that under socialism, in extremis, the state would tell you what job you had to take* and would decide how much you should get paid; I loathed this idea as I didn’t trust someone else to make those decisions about my life.

In 1979 we had a mock election at school in parallel to the general election. I felt allegiance to my working-class roots and so supported Labour. It was the first and only time. Through the early 1980s I began to support the Conservative party as they seemed to be closer to my own capitalist leanings, though I did disagree on some policy areas. For instance I was, like many others at that time, interested in the nascent Citizens’ Band (CB) radio scene that was emerging. The craze was spreading from the US driven by the popularity of the film Convoy. I wanted to join in but it was illegal. The new Tory government refused to allow a technology that would allow its people to talk to each other in a peer-to-peer networking arrangement: at this time government still owned all telecommunications, including where you could site the hard-wired rented telephone in your own house; it wasn’t until 1984 that BT was privatised and a duopoly created with Mercury Communications (a subsidiary of the also-recently privatised Cable and Wireless). Ideologically I couldn’t understand how the state could ‘own’ the electromagnetic spectrum, it just didn’t make sense: it was like owning the air! In 1981 the government relented and CB was legalised, but using a separate set of channels in a slightly-different frequency range to the rest of Europe and the US, who both had one common frequency standard. I think the riots and general concern the government had about insurrection prevented us in the UK being allowed to talk freely with foreigners!

One of my sixth-form school friends introduced me to the concept of the free market and Milton Friedman. I even remember laying on a sun-lounger one summer reading Free To Choose. I left for university and naturally joined the university’s ‘Conservative and Unionist Association’, chaired the previous year by a young John Bercow before he graduated. The fact that we were Tories at the ‘most left-wing university in the country’ fitted well with my contrarian, argumentative nature and individualist philosophy. The association wasn’t without its own excitement, the first meeting I attended in late 1985 included a vote of no-confidence in the association’s chairman, Stuart Millson due to his ‘robust patriotic’ views in the material he was publishing on campus.

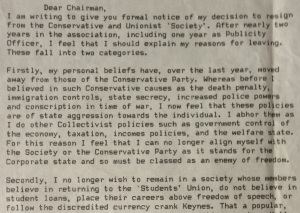

The history of the Federation of Conservative Students, of which we were members, is well documented. It was divided into three main groupings: the Wets, Authoritarians (mainly from the anti-immigration Monday Club) and Libertarians. I volunteered and joined my university’s association committee, eventually becoming its publicity officer and producing the association’s deliberately-inflammatory pamphlet (see below).

During this time I discovered the university library had a wealth of politics books of interest to me. Although I was there to study Electronic Engineering initially, although switched to Computer Science in year 2, my primary interest was politics and I read voraciously. I discovered John Stuart Mill, David Hume, Jeremy Bentham, Thomas Paine, Robert Heinlein, Ayn Rand, F. A. Hayek and eventually the authors of two books that changed my life: For A New Liberty by Murray Rothbard and Machinery Of Freedom by David Friedman. Through reading these books I discovered my natural libertarian home: anarcho-capitalism. It blended my dislike of authority and my belief in free trade in a consistent philosophy.

In this period I also found two sources of useful information: The Institute of Economic Affairs, to whose magazine I subscribed, and the Alternative Bookshop in Covent Garden, which I frequently visited. I remember a conversation at the bookshop one Saturday with Brian Micklethwait about taxation. I happened to mention that it was good to reduce the tax rates as this increased tax revenue**, an argument that we in FCS used to show that socialists only wanted high tax rates to punish the wealthy, not to help the poor. Brian rightly scoffed at me, asking why a libertarian would want the government to have more tax revenue. I realised that my libertarian-conservative position was inconsistent – sitting on the fence is a pain in the arse. I didn’t stay on that fence for much longer.

The last FCS conference I attended was in Leicester – I remember several of us standing waiting for a bus from the digs to the venue and chatting to FCS luminary Harry Phibbs, who was in trouble with Central Office at the time. He had published the FCS magazine New Agenda with an article by Nikolai Tolstoy about Lord Stockton (Harold MacMillan) sending 40,000 Cossacks back to their deaths in Russia after the end of World War 2. Calling a Tory party grandee a “War Criminal” on the front page of a journal published in Conservative Central Office was the last straw for the party: us self-styled ‘comrades’, we were often called the Troskyist entryists in the Tory party, had ‘gone too far’. FCS was shut down and replaced with a neutered tightly-controlled student group. The Leicester conference was infamous for its most extreme libertarian agenda under discussion. It was here that we passed the motion for free migration, unfettered migration in and out of the UK, completely anathema to the Monday Club-authoritarians and Wets. This show of strength by the growing libertarian caucus obviously frightened the party.

When it was announced that FCS was being closed I reviewed my beliefs and decided the Conservative Party was no longer a suitable place for an out-and-out libertarian, so I resigned.

The relevant portion of my resignation letter is included here:

Since that point, in May 1987, I have regarded myself only as a libertarian; that is a believer in the non-aggression axiom and its natural conclusion: anarcho-capitalism as described by Rothbard and Friedman. Although staying out of party politics, and avoiding voting in all elections, I continued to support the libertarian cause. After dropping out of university, and earning my first pay packet, I bought $300 of books from the Laissez Faire Books in New York; I still have all of these. Since the adoption of the internet I sought out fellow libertarians (posting on the topic on Usenet back as far back as 1993). After a while I lost touch with the libertarian movement, only checking the Libertarian Alliance’s website a few years back, until I discovered Twitter and discovered the joy of blogging.

Finally I discovered Libertarian Home in the last few months. It’s a great meeting place for like-minded libertarians around London and it’s good to be involved again in debating our various views on the philosophy. After a break away from politics I plan to stay involved now and I am even considering formal study in the subject.

* Yes, the similarity to Workfare doesn’t escape me!

** I now know this as the Laffer curve, having seen the concept presented recently by Arthur Laffer himself.